Cell study offers new clues to Dravet seizure triggers

Scientists find abnormal levels of elements linked to nerve cell function

Written by |

Lab-grown nerve cells from people with Dravet syndrome have abnormal levels of chemical elements that regulate nerve cell function, including potassium, copper, and zinc, a study found.

Researchers said these imbalances may contribute to abnormal brain electrical activity, which makes people with Dravet prone to seizures.

“These findings suggest that an elemental imbalance may be involved in the [disease development] of [Dravet syndrome],” the researchers wrote, noting that higher levels of potassium, copper, and zinc “have been implicated in seizure episodes and epilepsy.” Future studies may explore whether restoring normal element balance could become a potential alternative treatment strategy in Dravet, they said.

The study, “Dravet Syndrome Patient-Derived Neural Cells Present Altered Levels of Potassium, Copper, and Zinc,” was published in ACS Chemical Neuroscience by a team of researchers in Sweden, Denmark, and the U.K.

Gene mutations disrupt sodium flow

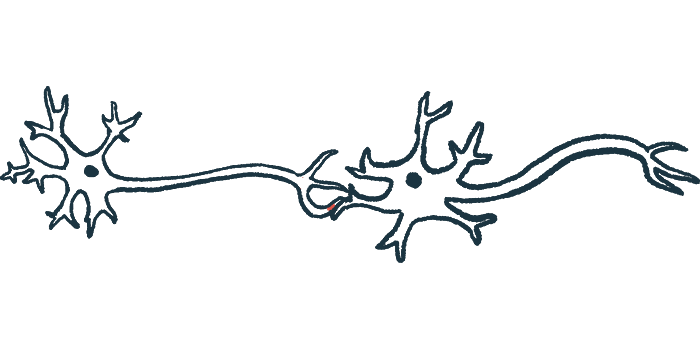

Dravet syndrome is caused in most cases by mutations in the SCN1A gene, which encodes a protein component of the brain sodium channel NaV1.1. These channels, found on the surface of nerve cells (neurons), control the flow of sodium ions into the cells, allowing them to generate and fire electrical signals.

When NaV1.1 doesn’t work correctly, less sodium enters certain neurons — especially inhibitory neurons, which normally help keep brain electrical activity in check — reducing their ability to send signals. As a result, other neurons in the brain become overly active, leading to seizures and other Dravet symptoms.

The balance of charged elements inside neurons is normally tightly controlled. Changes in chemical elements, such as calcium, zinc, copper, and magnesium, have been reported in other forms of epilepsy. The researchers wondered whether defects in the sodium channel might also disrupt brain levels of other important elements in Dravet syndrome.

To find out, the scientists used induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells derived from people with Dravet. These are stem cells created by reprogramming cells so they can develop into many different cell types. The researchers guided the iPS cells to form three-dimensional clusters of nerve cells, called neural-induced spheroids, which reproduce some early features of developing brain tissue. For comparison, they also created neural-induced spheroids derived from stem cells from people without the condition.

Unlike previous approaches that measured changes in blood samples, these neural spheroids allow researchers to directly examine what is happening inside developing nerve cells affected by Dravet syndrome, the researchers noted.

The team first confirmed that iPS cells in the spheroids had developed into nerve cells and showed the presence of sodium channels, including Nav1.1. They then measured the levels of different elements using a highly sensitive imaging technique.

Compared with spheroids derived from people without Dravet, patient-derived neural-induced spheroids showed significantly higher levels of potassium, copper, and zinc.

Potassium helps maintain the electrical balance across a neuron’s membrane, which influences how easily a nerve cell becomes active and sends signals. Although the researchers could not determine whether the higher potassium levels were inside or outside the cells, they noted that excess potassium outside neurons could make nearby nerve cells more likely to become active, increasing the brain’s susceptibility to seizures.

Zinc is stored in tiny compartments called synaptic vesicles at the ends of neuron extensions, where its release can influence how strongly nearby brain cells respond to signals. The researchers hypothesized that disrupted ion balance in Dravet syndrome cells may lead to abnormal zinc accumulation in these vesicles. If released in altered amounts, this could contribute to the excessive electrical activity in certain neurons observed in the condition.

Copper is important for brain development and function and helps certain enzymes protect neurons from oxidative stress, a type of damage that can occur during seizures. The researchers proposed that the higher copper levels detected in neural-induced spheroids derived from patients might reflect a response to this kind of stress. They also noted that copper can influence proteins involved in nerve signaling, including some that help regulate inhibitory brain activity. That means altered copper levels might contribute to the abnormal nerve cell activity seen in Dravet syndrome.

“To date, this is the first report on the elemental composition of Dravet-derived cells,” the researchers wrote. While they noted that cell-based studies have limitations, they added that “further studies might point toward the reestablishment of [potassium], [copper] and [zinc] levels, as a possible strategy to affect [Dravet syndrome] neural cells and, possibly, find an alternative way of treating and controlling this syndrome.”