Ketogenic Diet May Not Promote Neuropsychological Development in Dravet, Study Suggests

Written by |

Contrary to what was previously believed, the ketogenic diet — a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet— did not significantly promote cognition and neuropsychological development in children with Dravet syndrome over time, according to a study.

The study, “Efficacy of the ketogenic diet in Chinese children with Dravet syndrome: A focus on neuropsychological development,” was published in Epilepsy and Behavior.

Despite the development of anti-seizure medication, seizures in children with Dravet syndrome remain difficult to treat, leading researchers to investigate other therapeutic avenues, such as diet.

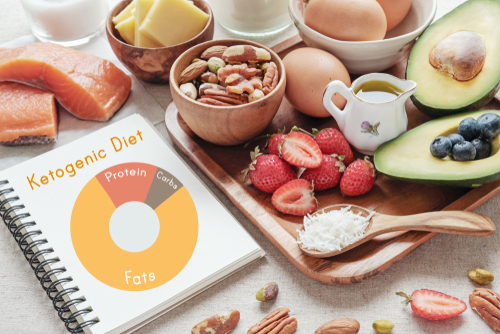

The ketogenic diet is a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet that involves drastically reducing carbohydrate intake and replacing it with fat. This change promotes the use of ketone bodies — compounds produced during the metabolism of fats — as a source of energy, which is thought to have an anti-epileptic effect.

The ketogenic diet has been used as treatment for children with epilepsy since the 1920s. The efficacy of the ketogenic diet for childhood epilepsy has been investigated and reported in several clinical trials. In fact, one trial showed that patients with refractory epilepsy who followed a ketogenic diet experienced an improvement in cognition.

However, most of the previous studies investigating the effect of the ketogenic diet on those with Dravet syndrome have been limited by the small number of patients enrolled. Furthermore, the impact of the ketogenic diet on the neuropsychological development of children with Dravet has never been compared with a control group.

Chinese researchers in this study investigated the effect of the ketogenic diet on seizure frequency in children with Dravet syndrome as well their neuropsychological development, as evaluated by Gesell developmental schedules. This scale uses direct observation to evaluate a child’s cognitive, language, motor, and social-emotional responses.

Researchers retrospectively analyzed three years of data from 26 children (14 male) with Dravet syndrome who were being treated with the ketogenic diet, comparing it with that of 40 children with Dravet who were not being treated with the ketogenic diet.

All patients had shown seizures resistant to at least two types of anti-epileptic drugs, and had been on the ketogenic diet for at least two months, in addition to their anti-epileptic medication.

At least one episode of status epilepticus — a condition in which a seizure lasts longer than five minutes or when seizures follow one another without recovery of consciousness between them — occurred in 20 of the 26 children (77%) before starting the ketogenic diet, and in only four of the patients (15%) after beginning the diet. In the non-ketogenic diet group, 27 patients (68%) experienced at least one episode of status epilepticus.

At three, six, 12, 18, 24, and 30 months after starting the diet, 92.3%, 84.6%, 46.2%, 30.8%, 19.2%, and 19.2% of the patients remained on the diet, respectively. At those points in time, 38.4%, 34.6%, 38.4%, 23%, 15.4%, and 15.4%, respectively showed a seizure reduction of more than 50%.

Of the 26 participants, 12 were assessed using the Gesell developmental schedules before and after starting the ketogenic diet. The mean age at diet start was 3 years, and diet duration ranged from three to 24 months.

The development quotient (a numerical indicator of a child’s growth to maturity across different psychosocial competences) at the first evaluation was significantly higher than at the second evaluation in all five fields of the Gesell scale: gross motor, fine motor, adaptive behavior, language, and personal-social ability. Fine motor scores were most affected.

However, the children continuously acquired new abilities (increase in development age), which was also noted by their parents.

“We found a decline of [development quotient] subscores following KD [ketogenic diet], which suggests that neuropsychological developmental delay worsens progressively with age when compared with typical children at the same age, despite the addition of the KD,” the researchers wrote.

Importantly, no significant differences of development quotient changes over time were observed between children treated with the ketogenic diet and those who were not.

However, the study did have some limitations, namely the fact that since the ketogenic diet is a second-line therapy for Dravet syndrome, seizures in the patients on the diet were more severe than those in the non-diet group.

“We can see that cognitive and other neuropsychological developmental aspects improved after KD, but that no significant difference was observed when compared to a non-KD group with DS [Dravet syndrome]. The effect of KD on neuropsychological development of DS patients is therefore worthy of further investigation,” the researchers concluded.